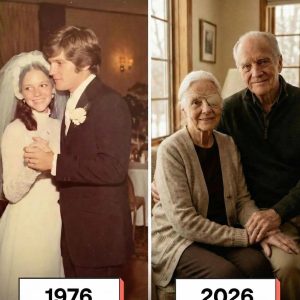

The passage of twenty years has a way of smoothing over the jagged edges of a tragedy, turning a sharp, stabbing pain into a dull, rhythmic ache. I am seventy years old now. I have lived long enough to bury two wives, outlive most of my childhood friends, and grow accustomed to the heavy, quiet dust that settles on a life once filled with noise. I thought I had mastered the art of survival, but grief is a deceptive thing; it doesn’t leave, it simply waits for the right moment to reveal that you never truly understood its cause.

The winter of 2006 was particularly cruel. It was just a few days before Christmas when my son Michael, his wife Rachel, and their two children, Sam and Emily, came over for an early holiday dinner. I lived in a small, tight-knit town where the rhythm of life was dictated by the seasons. The forecast had promised light flurries—the kind that makes for a picturesque postcard—but the sky had a different plan. By the time dinner was over, the wind had begun to howl with a predatory edge.

Michael stood in the entryway, adjusting the hood on five-year-old Emily’s puffy jacket. He gave me that confident, lopsided grin he’d worn since he was a teenager. “We’ll be fine, Dad,” he insisted, dismissing my concerns about the worsening visibility. “I want to get the kids tucked in before the drifts get too high.” I watched their taillights vanish into a white curtain of snow, and for the first time in my life, I felt an inexplicable, cold dread coil in the pit of my stomach. It was an alarm that arrived too late to be of any use.

Three hours later, the knock came. It wasn’t the rhythmic tapping of a neighbor; it was sharp, official, and final. Officer Reynolds stood on my porch, his uniform caked in ice, his expression a practiced mask of somber empathy. He told me the rural road Michael had taken—a shortcut he’d used a hundred times—had iced over completely. The car had skidded off the shoulder and into a stand of old-growth timber. Michael, Rachel, and eight-year-old Sam were gone before the first responders could even reach the site. Only little Emily, tucked into the back seat, had survived.

The weeks that followed were a blur of fluorescent hospital lights and the hollow ringing of a church bell. The doctors told me that the trauma had likely caused a dissociative fog; Emily remembered fragments of the night, but the core of the accident was lost to her. “Don’t push her,” they warned. “Let the memory return on its own, or let it stay buried.” So, I let it stay buried. At fifty, I traded my quiet retirement for the chaos of raising a traumatized kindergartner. I learned to braid hair without snagging, I learned to navigate the aisles of toy stores, and I learned to answer her heartbreaking questions with a script I had memorized to keep myself from breaking: “It was an accident, sweetheart. Just a bad storm. Nobody’s fault.”

Emily grew into a quiet, observant woman. She had a mind like a steel trap and a penchant for puzzles that made her a natural for the legal profession. When she returned home after college to save money, working as a paralegal at a local research firm, our lives fell into a comfortable, predictable rhythm. But as the twentieth anniversary of the crash approached, the air in the house changed. Emily became distant, her gaze lingering on old family photos with an intensity that bordered on clinical. She started asking questions that felt like needles under the skin. She wanted to know the exact time they left, the specific badge numbers of the officers on the scene, and why the police reports seemed so brief.

One Sunday afternoon, she sat me down at the kitchen table—the same table where she had once colored holiday drawings while I wept in the pantry. She slid a folded piece of paper toward me. Her hands, usually so steady, were trembling. On the paper, in her precise, elegant handwriting, were four words: “IT WASN’T AN ACCIDENT.”

My first instinct was to offer a patronizing laugh, to tell her she was overthinking a tragedy that had been settled decades ago. But the look in her eyes stopped me. It wasn’t the look of a grieving granddaughter; it was the look of a hunter who had found the trail. She reached into her bag and produced a relic—a silver flip phone, scratched and dated, the kind that had been obsolete for a decade. She had found it in a mislabeled box in the county archives while doing research for her firm. It had belonged to her father.

“There are voicemails, Grandpa,” she whispered. “Messages that were supposed to be deleted. But the server data was never fully purged from the hardware.”

She pressed play. Through a storm of static and the muffled roar of an engine, I heard a man’s voice, jagged with panic: “—can’t do this anymore. You said no one would get hurt.” Then, a second voice—cold, authoritative, and terrifyingly familiar—responded: “Just drive. You missed the turn. Keep them moving toward the pass.”

The floor seemed to tilt beneath me. Emily explained what her months of digging had uncovered. Officer Reynolds, the man who had delivered the news with such “empathy,” had been the subject of a hushed internal investigation at the time. He had been on the payroll of a regional trucking company, taking bribes to keep certain dangerous, unmaintained routes open for their drivers to avoid weigh stations. On the night of the crash, a massive semi had jackknifed across the shortcut. Instead of barricading the road, Reynolds had been instructed to “clear the scene” quietly. He had redirected traffic, including my son’s car, directly toward the hazard in a desperate bid to hide the trucking company’s negligence before the storm grew too heavy.

“They didn’t just slide off the road, Grandpa,” Emily said, her voice cracking for the first time. “They swerved to avoid a ghost. A truck that shouldn’t have been there on a road that should have been closed.”

The revelation shattered the foundations of my grief. For twenty years, I had blamed the weather. I had blamed Michael for leaving too late. I had even blamed myself for not insisting they stay. To realize that their deaths were the collateral damage of a corrupt officer’s paycheck was a new kind of agony. Reynolds had died of a heart attack years ago, escaping legal justice, but the truth had finally been unearthed by the very child he thought wouldn’t remember.

Emily reached into her bag one last time and pulled out a faded manila folder. It contained a letter from Reynolds’ widow, found among his private papers after his death. In it, the woman confessed that her husband had been haunted by that night until his final breath. He hadn’t expected a family to be on that road; he had only been thinking of the debt he owed the company. The letter wasn’t an excuse, but it was a confirmation.

That night, for the first time in two decades, the silence in our home didn’t feel heavy. We sat together, the old man and the brilliant woman he had raised, and we talked about Michael’s laugh and Sam’s drawings and the way Rachel always smelled like cinnamon. The truth didn’t bring my son back, but it stripped away the shame and the mystery that had haunted our lives. As the snow began to fall outside the window—soft, harmless flurries—I realized that Emily hadn’t just survived the crash; she had mastered it. She had looked into the darkness of our family’s history and brought back the light. I pulled her into a hug, feeling the strength of the woman she had become, and realized that while I had spent twenty years raising her, she was the one who had finally saved me.